In aerospace defense circles, the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) has seized an outsized role in worldwide debate since the Trump administration took office, becoming a flashpoint topic for international tension and speculation regarding U.S. trustworthiness as a defense supplier.

Last month, widely-circulated false rumors of a U.S. “kill switch” on exported F-35 fighters forced Lockheed Martin and the F-35 Joint Program Office (JPO) to issue statements disavowing the notion. Several foreign F-35 participant nations reaffirmed their ability to fully and independently operate their aircraft. Yet, the kerfuffle raised concerns abroad about the U.S. potential to cut off software updates and parts sowing skepticism, particularly in Europe, about whether the U.S. is a reliable partner for long-term F-35 fleet support.

With the Trump Administration’s tariff-heavy policies injecting near daily unpredictability into the worldwide market, concern is growing over the program. In an industry increasingly defined by international collaboration, the F-35’s sprawling global supply chain and network face real questions about stability and longevity.

A Far-Reaching Venture

The F-35 is the Pentagon’s most ambitious and expensive aircraft in military history. In FY25 alone, the DoD requested $12.4 billion for the program with $70.1 billion projected through 2029. Over the program’s expected 94-year lifespan, the U.S. plans to procure 2,456 units, with an estimated total program investment, including foreign contributions, of $2.1 trillion.

Beyond its military value, the F-35 is an economic engine. Lockheed Martin calls it the most “economically significant defense program in history” supporting over 250,000 manufacturing jobs and generating $72 billion per year. That footprint places the F-35 program among the world’s top 80 economies by GDP.

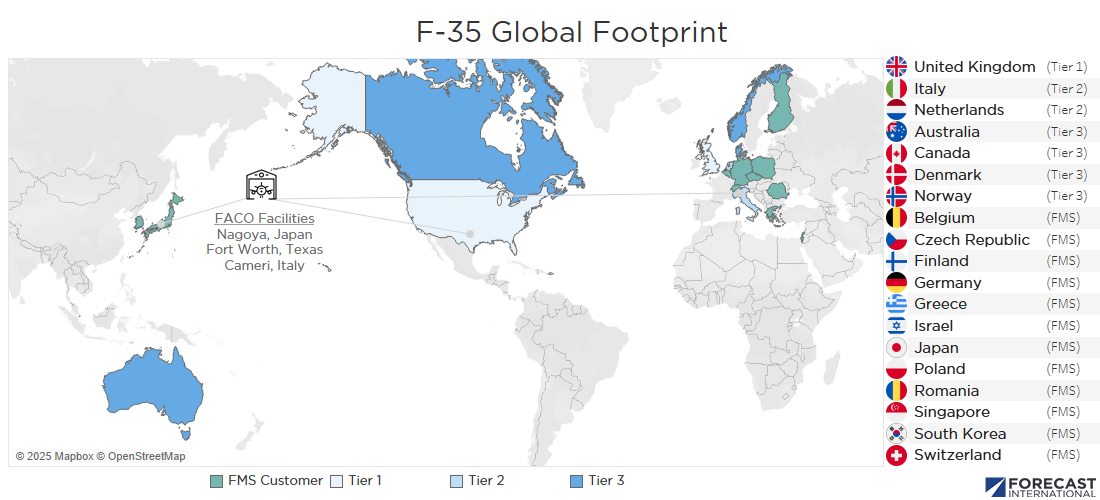

Including the U.S., 20 nations are either tier partners or Foreign Military Sales (FMS) customers. Over half of those countries are integrated into the F-35 manufacturing process either as component suppliers or planned industrial participants.

From its inception, the F-35 project has represented a truly multinational effort. The U.K., Italy, and the Netherlands joined as core development partners in the early 2000s contributing billions in funding. As the only Tier 1 partner, the U.K. is a vital teammate on the F-35, owning at least 15 percent of the aircraft’s production value. British BAE Systems is a primary supplier and Rolls-Royce exclusively builds the F-35B LiftSystem that drives the Bravo’s unique short take-off and vertical landing (STOVL) capability.

Australia, a Tier 3 partner, announced this month that over AUD5 billion in F-35-related contracts have been awarded to Australian industry over the life of the program, with contributions from more than 75 Australian companies.

Including the U.S., 20 nations are either tier partners or Foreign Military Sales (FMS) customers. Over half of those countries are integrated into the F-35 manufacturing process either as component suppliers or planned industrial participants.

Aside from the main Forth Worth, Texas factory, international Final Assembly and Check-out (FACO) facilities are located in Cameri, Italy and Nagoya, Japan where engines and control surfaces are fitted. Construction on additional foreign F-35 facilities is ongoing including a Patria F135 engine depot in Finland and a Rheinmetall fuselage plant in Germany scheduled to begin production this month.

On Tariffs

The defense sector typically benefits from insulation compared to the commercial aerospace market’s volatility. Defense supply chains are generally more protected from market fluctuations, particularly among programs paramount to U.S. national security like the F-35. Moreover, it’s possible that the Trump Administration has or will exempt certain components or materials critical for maintaining production of strategic weapons systems.

However, there is still cause for concern given the F-35’s global footprint and complex web of logistics and manufacturing support abroad. Any corresponding tariff effects are likely to relate to raw or sourced materials rather than advanced manufactured components. According to a recent International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) report on rare-earth elements (REE), numerous REEs and metals are utilized to build the F-35 and its sub-systems.

The U.S. imports approximately half of its aluminum, most of it from Canada, which has received Trump’s recent political attention. Aluminum is used in the airframe structure and comprises roughly five percent of the F-35 exterior. Amid diplomatic tension with the U.S., Canada is reviewing its 2023 plan for 88 F-35As. Although financially committed to 16 fighters, Canada could shrink its overall acquisition plan as a result.

At least as late as 2022, a Chinese-sourced alloy was used in a subcomponent for the F-35 engine prompting a Pentagon-issued waiver, underscoring the program’s dependence on foreign suppliers. The IISS’ analysis notes that China supplies several types of REEs used in F-35 equipment to the U.S. and Europe. While an escalating trade war of reciprocating tariffs between the U.S. and China might not apply to specific F-35 components, it could pressure domestic and international subcontractors to raise prices or even drop out of the program entirely.

Uncertainty Abounds

In late 2023, Pittsburgh-based Howmet Aerospace, a key supplier of F-35 airframe and engine parts, was sued by Lockheed Martin after it halted titanium deliveries. Howmet cited sourcing price hikes resulting from the Russian invasion of Ukraine for the disruption. The dispute was later settled, but the incident illustrates the impact of external economic circumstances jeopardizing critical defense supply chains.

Now, it’s plausible that a similar story could play out. According to reporting from Reuters this month, Howmet Aerospace issued a letter to customers citing force majeure and notifying them that shipments could stop because of tariff impacts. While the letter may be limited to the commercial market, military programs like the F-35 are not fully immune.

As of this week, China has reciprocated Trump’s 145 percent tariff on Chinese goods with a 125 percent levy on U.S. imports and suspended REE and magnet exports utilized by American aerospace companies.

Even if defense supplies are exempted from the tariffs, F-35 program costs could increase. Economists generally believe, at least in the short-term, that an escalatory tariff war will drive up inflation. According to the JPO, roughly half of the lifetime $2.1 trillion F-35 program estimate is attributed to inflationary effects. If the tariffs lead to general inflation, those costs are likely to pass on to F-35 customers, namely the DoD and allied buyers.

Despite any real or perceived economic and political pressures, the F-35 remains the most capable and combat-tested fifth-generation fighter on the export market. Its performance capabilities, multinational support structure, and decades of joint development and investments make it an unrivaled and resilient defense product.

Foreign customers considering divestment from American defense programs due to the Trump Administration’s actions face difficult tradeoffs. While alternatives might offer greater independence and lower procurement costs, none match the F-35 program’s demonstrated advanced technology and global scope. In defense, a superior high-end product can be too hard to pass up, often worth the cost of any side effects.

Join Forecast International at the Paris Air Show to gain valuable insight into the evolving dynamics of the global defense market. Traditionally regarded as insulated from broader economic fluctuations, the defense sector is now increasingly impacted by global economic forces. Tariffs, trade disputes, and rising economic nationalism are introducing new complexities that affect the stability, cost-efficiency, and resilience of critical defense programs.

For over 50 years, Forecast International has been a trusted authority in aerospace and defense intelligence. Our mission is simple yet vital: to equip industry leaders with the data-driven insight and strategic foresight needed for confident, informed decision-making. Visit us at Hall 3, Booth C164 to learn how our expert analysis can strengthen your planning and elevate your strategy.

Schedule a time with Jon in Paris.

A former naval officer and Seahawk helicopter pilot, Jon currently leads the Military Aerospace and Weapons Systems group at Forecast International. He specializes in current and emerging military fixed and rotary-wing aircraft. With over a decade of experience in military aviation, operations, and education, he forecasts a diverse range of defense and naval systems.

Influenced by his time as a former Presidential Management Fellow and International Trade Specialist at the Department of Commerce, Jon gained insights into government operations and global markets.

Before joining Forecast International, he served as an NROTC instructor and Adjunct Assistant Professor at the University of Texas, teaching undergraduate courses in naval history, navigation, defense organization, and naval operations and warfare.