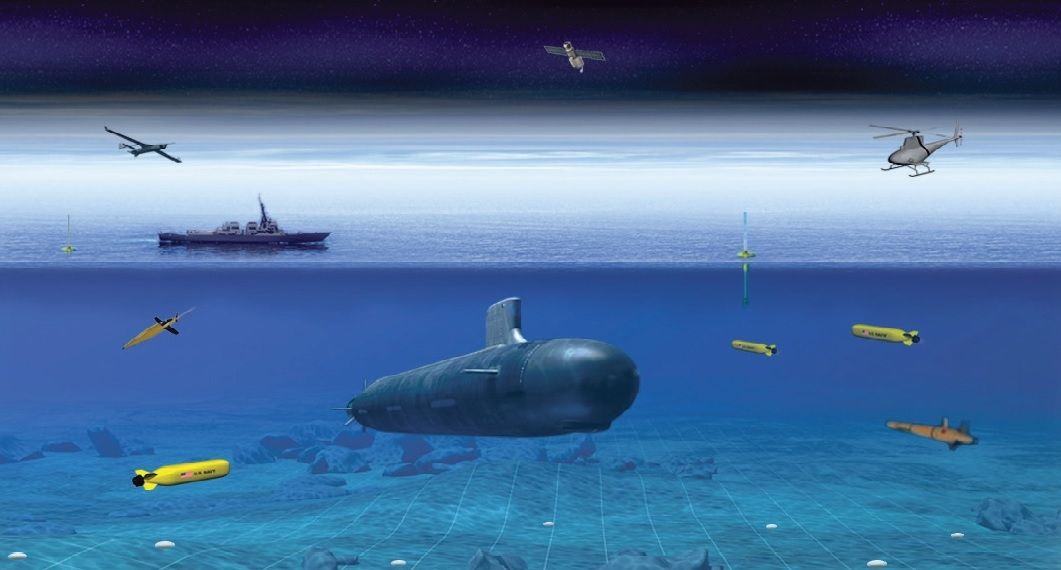

A common enough saying amongst sailors that still exists today is that undersea warfare essentially boils down to two things, the predator – submarines – and the prey – targets. The battle between a submarine and an anti-submarine system (be it another submarine or a surface ship) is a matter of obtaining sonar contact that is accurate and stable enough to allow the launch of a torpedo to prosecute that contact. Other undersea warfare weapons exist, as do other sensors, but it is torpedoes and sonar that hold pride of place.

The equipment used in undersea warfare are complex and require extensive research and development to support and operate. While small niche companies can maintain their position by investing in a tightly defined segment, only larger groups have the resources for a broader approach. If larger groups need the niche technology in question, it is simpler – and cheaper – to buy the company that invented it than to duplicate the research. Thus, a cyclic trend emerges that sees corporate diversification as technology development drives the creation of small niche companies, followed by consolidation as those companies are absorbed by the industry giants. The first two decades of this century appear to have ushered in a new diversification phase. That segment process now seems to have reached a plateau, suggesting that a new series of mergers and acquisitions may begin.

Following the United States’ withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021, there was a significant decrease in land warfare. As a result, the undersea warfare market — specifically the submarine segment — began rapidly picking up momentum as the operational significance of a submarine fleet sunk in. Navies across the world have begun to realize that the possession of operational submarines is the surest and most certain way of marking their transition from a local to a regional power. This is a logical perception since few other naval assets are quite as cost-effective as even a small force of submarines. Two or three submarines can establish a presence in an area of naval operations that is made all the more influential by their invisibility. Unless the submarines can be spotted in their base and accounted for, they exert a vague, indefinable menace that impacts every form of naval operation. This impact rises exponentially with the number of submarines in the fleet. Once the naval presence is established, other forms of naval assets become important, but as potential ship-killers, the submarine is hard to equal.

The ship-killing capability of modern submarines means that they are a major component of the offensive capability displayed by a fleet. Thus, to be taken seriously as a regional naval power, a country has to deploy a viable SSK force.

Nuclear-powered attack submarines take this ship-killing capability and add unprecedented strategic mobility that allows rapid worldwide deployment. In order to qualify as a world naval power, a nation has to operate SSNs. Thus, the acquisition of diesel-electric submarines turns a coastal patrol navy into a regional power. Adding nuclear-powered submarines makes that navy – and the country it serves – a world power. These political considerations drive submarine demands as effectively as any operational or strategic motivations.

Smaller navies must balance the heavy cost of maintaining an undersea warfare capability against naval demands to fulfill operational requirements of greater immediate concern. Early in the 21st century, Denmark made precisely this evaluation and came to the conclusion that it could no longer justify the investment needed to support an underwater warfare capability and that the funding in question would be better spent on improving the surface fleet. However, Denmark reversed its 20-year-old decision in June 2023 and is now seriously considering reactivating its defunct submarine service. The about-face in policy stems from Russia’s aggressive invasion of Ukraine and the fact that Russia’s Baltic Sea fleet has to pass through Denmark’s waters to get to the North Atlantic. In the past, Denmark relied on the capabilities of allies to cover undersea warfare while it concentrated on being part of Europe’s main battle tank coalition.

Submarine construction has been growing for the last several years, indicating that the operational significance of a submarine fleet is truly being realized. Navies around the globe have begun to perceive that the possession of operational submarines is the surest and most certain way of marking their transition from a local to a regional power – with China being an excellent example.

The undersea warfare market reflects the various undersea warfare systems, such as ASW systems, combat management systems, mine warfare and mine countermeasures systems, torpedoes, and various unmanned undersea vehicles. Over the past nearly two decades, the undersea warfare market has been sidelined by land-based international events (such as the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan) and threats. However, thanks to the increase in projected submarine construction — driven by Chinses expansionism in the South Pacific — undersea warfare is now receiving the attention it deserves and more importantly what it needs.

It should also be noted that the torpedo market — especially the heavyweight torpedo segment — is strongly influenced by submarine procurement patterns. The sale of a given submarine can usually signal what torpedo the customer will purchase. In the past, German-built submarines were armed with German torpedoes and French boats with French-made torpedoes. Today, European-built submarines are generally armed with European torpedoes. Still, despite the close relationship between continental submarine and torpedo manufacturers, there are no absolutes in this market.

For more than 30 years, Richard has performed numerous roles as a top analyst for Forecast International. Currently, Richard is the Group Leader and Lead Analyst for Forecast International's Traditional Defense Systems, which covers all aspects of naval warfare, military vehicles, ordnance and munitions, missiles, and unmanned vehicles.

Having previously been Forecast International's Electronics Group Leader for 20-plus years, Richard established Electro-Optical Systems Forecast, as well as having been the prime editor of Electronic Systems Forecast, Land & Sea-Based Electronics Forecast, and C4I Forecast. Additionally, Richard has served as the Naval Systems Group Leader responsible for Anti-Submarine Warfare Forecast andWarships Forecast.